Mark

DRAGIŠA VITOŠEVIĆ (1935–1987), WRITER, LITERATURE HISTORIAN, AND HIS ORPHEUSES AMONG PLUM TREES

Contributor from Gruža to Europe

He departed exactly thirty-five years ago, but his ”Raskovnik” magazine, his literary and scientific works remained an unsurpassable value of Serbian culture. He discovered and supported the lavishing gift of peasant-poets, the poetry radiated by the rooted gold coins of the language, mythical experience of life and death, love and purpose of existence in the fields, in the grass, in the universe. The profound longing for beauty. He dealt with the purity of language. He believed that the parvenu nature of our man was the main cause of vulgarity and moral offenses. He expressed anger and powerlessness only once. And had never recovered from it

By: Dragan Lakićević

Photo: Private Archive

I had just completed the gymnasium. Spent most of the summers in poetry. In autumn, off to Belgrade to study literature.

I had just completed the gymnasium. Spent most of the summers in poetry. In autumn, off to Belgrade to study literature.

– To become a writer – tells me Momir Vojvodić, young literature professor, who already has three printed books of poetry.

He knows that I note old words and folk tales and sayings: curses and blessings. Why are there more curses than blessings, more evil than good in the language?

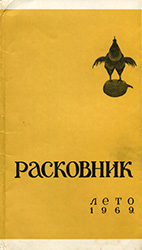

We are sitting at Momir’s desk in former Titograd. On the table is Raskovnik, magazine for literature and culture in rural areas, pocket format, like a scrapbook, green color – spring edition.

– Here, take it to Morača, read it during the summer. You have the address there, send them something! – says my older poet-friend.

I spent all my school holidays in Morača, on my grandfather’s estate, at my aunt’s – in the dawn of nature and stories, in the vicinity of the old Nemanjić lavra, with icons and frescoes of lavishing beauty.

I spent all my school holidays in Morača, on my grandfather’s estate, at my aunt’s – in the dawn of nature and stories, in the vicinity of the old Nemanjić lavra, with icons and frescoes of lavishing beauty.

Everything in Raskovnik was there to please me: words, poems, stories, folk customs, legends. The summer edition, all dressed in the gold of linguistic wheat.

I typed my poems and curses I heard from older women and shepherds when they yell at their cattle, and sent them to the address from the publisher’s page: Dragiša Vitošević, for Raskovnik magazine, village of Bare, Gruža, Serbia.

Not much time had passed, and a former postcard arrived at the small post office of Morača Monastery, the cheapest postal card, light yellow-green, with Slovenian and Macedonian name ”poštanska kartička”. Address: Dragan Lakićević, village of Bare, Morača Monastery.

Dear namesake,

Dear namesake,

We are namesakes because people call me Dragan too, and our villages are namesakes: Bare in Morača and Bare in Gruža. Your monastery is Morača, mine is Vraćevšnica. I received your contributions for Raskovnik and we will publish them in the autumn edition. I would like you to continue being our associate.

Regards from Dragiša Vitošević.

I was so happy I could fly. An editor in chief is writing to a distant and unknown boy as if we were family.

In the autumn, Students’ Square, between the faculties of Philosophy and Philology, handsome and slim poet Dobrica Erić is standing with two companions. We had met recently, at ”Young May” in Zaječar – that was the name of the festival of young poets of Yugoslavia.

– Dragan, let me introduce you to Dragan! – He turns to Vitošević: – Dragiša, this is Dragan Lakićević, poet, and this is editor in chief of Raskovnik, Dragan Vitošević!

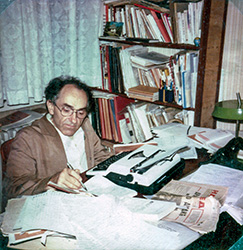

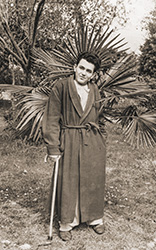

– We have already written to each other – said the short man with a big forehead and warmhearted smile, leaning on a cane: he was severely disabled. He turned very slowly.

RASKOVNIK PEOPLE

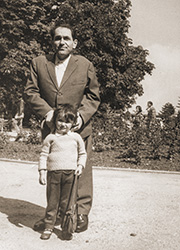

Dragiša Vitošević (1935–1987) was a literature historian and writer. Editor. He graduated from the Faculty of Philology and gained a PhD degree with the thesis ”Serbian Poetry 1901–1914”. He further studied in France and Russia. He worked in the Institute of Literature and Art in Belgrade.

Dragiša Vitošević (1935–1987) was a literature historian and writer. Editor. He graduated from the Faculty of Philology and gained a PhD degree with the thesis ”Serbian Poetry 1901–1914”. He further studied in France and Russia. He worked in the Institute of Literature and Art in Belgrade.

In the year 1968, with a group of professors and poets, he started Raskovnik, magazine for literature and culture in rural areas. Their associates were many village poets, as well as others, especially ethnologists, rural sociologists and linguists. He discovered the lavishing talent of many peasant-poets: anticipating the mass departure from villages to cities and dying of the original rural life in the fields and language, the poets of that time celebrated nature and earth in an unrepeatable way. Some of them, such as Dobrica Erić from Donja Crnuća, Milena Jovović from Dobrača, and Srboljub Mitić from Veliki Crljeni near Požarevac, became some of the best Serbian poets of their generation. The first who supported them, wrote about them, and interpreted their words and thoughts was – Dragiša Vitošević.

In the poetry of peasant-poets, the rooted golden coins of language spoke and radiated, mythical impulses of life and death, love and purpose of existence in the fields, in the grass, in the universe… In the womb of the field! Dragiša Vitošević recognized and felt, described and praised all that: ”From Erić’s verses, from that entire world, a profound, muffled, primal longing for beauty is bursting out: everything that is taken out, born, entrusted, whatever the magical wand of poetry touches – must primarily be convenient and skillful, worthily shaped and ’dressed’… chronicle writer, he is also an uncurable admirer of everything unreachable, loner and

In the poetry of peasant-poets, the rooted golden coins of language spoke and radiated, mythical impulses of life and death, love and purpose of existence in the fields, in the grass, in the universe… In the womb of the field! Dragiša Vitošević recognized and felt, described and praised all that: ”From Erić’s verses, from that entire world, a profound, muffled, primal longing for beauty is bursting out: everything that is taken out, born, entrusted, whatever the magical wand of poetry touches – must primarily be convenient and skillful, worthily shaped and ’dressed’… chronicle writer, he is also an uncurable admirer of everything unreachable, loner and  melancholic, sometimes the cursed one. Explorer of the vast spaces of our peasant country and its destiny, he, I will admit, knew how to reveal to me unimagined spaces of its pain and struggling…”

melancholic, sometimes the cursed one. Explorer of the vast spaces of our peasant country and its destiny, he, I will admit, knew how to reveal to me unimagined spaces of its pain and struggling…”

With his profound insight in poetry, Dragiša defends poetry and entire creativity in rural areas – from spite and mocking of city intellectuals, who don’t have a feeling for images of weaving or threshing, which depict the drama of pulses of a sensitive being in the rhythm of agricultural tools and sound of the reaping-hook in the silk of wheat.

Raskovnik had an immediate success. The high circulation of the first edition was immediately sold and the second edition printed – it had never happened with any magazine, which, by the way, was published in Gornji Milanovac. Raskovnik became the gathering point of creativity in rural areas and its main creator was Dragiša Vitošević.

To inform the world about the achievements of village poets, Dragiša, together with Dobrica Erić, edited a collection of Serbian village poets entitled Orpheus among Plum Trees. It was published by Svetlost from Kragujevac in 1963.

HE THOUGHT DIFFERENTLY

Dragiša began his literary work with prose. His book of short stories was published by Matica Srpska in 1966, entitled Serious Games. In tiny letters and Latin alphabet, good old Matica tried to be common in those times: in the spirit of brotherhood and unity.

Dragiša began his literary work with prose. His book of short stories was published by Matica Srpska in 1966, entitled Serious Games. In tiny letters and Latin alphabet, good old Matica tried to be common in those times: in the spirit of brotherhood and unity.

People, homeland, village, war, poverty – those were the frames of Dragiša’s poetry… The realistic weft of his early short stories continues with Kosovo legends and documentary narrative miniatures, often anecdotes about the people and its phenomena of ethics, customs, echoes of legends in contemporary life. These proses make a book of ”a hundred short stories” Oxen on the Ceiling, which were, together with several more manuscripts from his heritage, published by Dragiša’s wife Vjera and daughter Nevena Vitošević. Dragiša published those short lessons, contemporary examples of valor and heroism, moral lessons or mockeries, in Politika, so that as many people as possible could read them, recognize themselves in them and be warned. To be taught or ashamed.

Dragiša published serious scientific books: his PhD thesis Serbian Poetry 1901–1914, a book of polemic texts I Think Differently, essays about self-taught creative work Contributors from the Shadows, a book of essays about Serbian literature To Europe and Back (1–2) and others.

He dealt with the purity of language, helped poets, chose words, replaced foreign words with local – whenever it was possible. He claimed that one must know many of our words and languages, in order to write originally…

He dealt with the purity of language, helped poets, chose words, replaced foreign words with local – whenever it was possible. He claimed that one must know many of our words and languages, in order to write originally…

The main cause of vulgarity, as well as ethical offenses, Dragiša saw in the parvenu nature of our man. Parvenuism is the ”illness of our society and our culture” – writes Dragiša in his book I Think Differently (1983). A parvenu writes in Latin letters, because they think it’s more trendy and closer to European culture. With parvenuism and fad, man and society abandon traditional values. A parvenu is the main hero of Dragiša’s obsessions and his exposition at many literary events and social-political counsels. In them he cares about the folk language and entire Vuk’s heritage…

As member of the Radio Television Belgrade Commission for Serbo-Croatian Language, Dragiša wrote two letters to powerful and reputable Milan Vukos, director of RTB, turning his attention to ”lack of action” in cherishing ”our (poor) language” on the radio, particularly on the omnipresent television, but the television didn’t want to publish those letters, and newspapers didn’t dare to.

As member of the Radio Television Belgrade Commission for Serbo-Croatian Language, Dragiša wrote two letters to powerful and reputable Milan Vukos, director of RTB, turning his attention to ”lack of action” in cherishing ”our (poor) language” on the radio, particularly on the omnipresent television, but the television didn’t want to publish those letters, and newspapers didn’t dare to.

Dragiša writes to newspapers, fights, argues, comments – about issues such as: books in the village and the city, workers in literature, language, Vuk’s Award and Vuk’s spirit, school, textbooks, dumbing down the media, whose is Njegoš?, petty bourgeoisie and bureaucracy, epidemic of parvenuism…

The book I Think Differently is full of Dragiša’s everyday fights for literary-linguistic and cultural justice at every step of public life.

CENTURY OF RURAL VERSEMAKING

Dragiša Vitošević wrote a voluminous and systematized history of Serbian poetry in rural areas, entitled Contributors from the Shadows (1984). In it, as a reliable scientist, as well as a well-informed expert in the village, life, creative work and language, he set the context of creating art in the village, with all the phenomena of such creativity: picturesqueness and way of thinking, or wisdom – from singing by the cradle and while working, to artwork in carpetmaking, naïve painting, embroidery, making clothes, distaffs and other objects. That is how the essay about Obrenija from Bogdanica was created – a woman for all village works, as well as artistic and spiritual talents.

Dragiša Vitošević wrote a voluminous and systematized history of Serbian poetry in rural areas, entitled Contributors from the Shadows (1984). In it, as a reliable scientist, as well as a well-informed expert in the village, life, creative work and language, he set the context of creating art in the village, with all the phenomena of such creativity: picturesqueness and way of thinking, or wisdom – from singing by the cradle and while working, to artwork in carpetmaking, naïve painting, embroidery, making clothes, distaffs and other objects. That is how the essay about Obrenija from Bogdanica was created – a woman for all village works, as well as artistic and spiritual talents.

Dragiša processed an entire ”century of rural versemaking” – oral chronicle writers of the village, a peasant-poetess from 1833, poets from old periodic magazines, even legendary versemaker Vlaja from Glibovac, spiritual brother of Danojlić’s Dobrislav and many Serbian poets-sufferers from the 20th century. There are ”rural Orpheuses” and rural ”paths of prose”, ”visual arts and other subjects”, registers. Dragiša left all that to the conscience of Serbian culture in the future. Thus was his entire endeavor: to leave behind, for the people to know.

The spans and reaches of the scientific approach to Serbian literature are best seen in two comprehensive volumes of Dragiša’s book To Europe and Back, in almost 1.300 pages… As if he had been writing his entire life – about many, almost all great Serbian writers and works and their meanings and European values and achievements. Dositej and Vuk meet Europe as well. Dragiša notes the experience of Europe of our greatest people from the 19th century. That entire century passed ”in abhorring from Europe, always enslaving”, writes Vitošević. Serbian belonging to Europe represents a complex subject. And Serbian language sends Europe its epic poetry (Višnjić and Milija), Vuk, Sarajlija, Njegoš, Sterija, Zmaj and others. The review To Europe and Back is a large collection of essays and studies on chosen subjects and from specific points of view. Dragiša’s comprehensive history of Serbian literature.

VENTURER

That autumn edition of Raskovnik (1972), with my poems and curses from Morača, was published, but only for a short time. It was canceled and publicly politically attacked because of the poem ”Marching to Kosovo” written by Milena Jovović from the village of Dobrača. Kosovo was a sensitive subject for which Serbian communists had to stand before their own deity. The magazine was not forbidden, but it was denied financial means and it soon stopped being published.

That autumn edition of Raskovnik (1972), with my poems and curses from Morača, was published, but only for a short time. It was canceled and publicly politically attacked because of the poem ”Marching to Kosovo” written by Milena Jovović from the village of Dobrača. Kosovo was a sensitive subject for which Serbian communists had to stand before their own deity. The magazine was not forbidden, but it was denied financial means and it soon stopped being published.

For the second time, Raskovnik was renewed in 1979 within Narodna Knjiga publishing. Dragiša and Dobrica, as well as professor-translator Vladeta Košutić, stayed from the old editorial desk, and were joined by young researcher of incantations and legends, later member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Ljubinko Radenković, and the writer of these memories.

Dragiša Vitošević was the first to remember that the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo is in just a few years. Together with the writer of these lines, he wrote an invitation to publishers and cultural institutions to prepare for it: we suggested an abundance of political and state issues, subjects and areas in which the myths of Kosovo, signs and authors created great works. We mentioned poetry and history, ethnography, music and Lubarda. No one dared to respond – the spoons from the students’ canteen in Priština were still rattling, in which young Albanians in 1981 called for an uprising which is still lasting. The communist authorities wanted to hide all that and quiet it down in their own way, so they lied about everything for a long time...

He loved local folk words. He would choose one and then repeat it to anyone he met that day or that month, as if he were sowing. I once met him three times in one day and each time he mentioned the world venturer. He was actually a venturer: hardworking, diligent, entrepreneurial man (Dictionary of Matica Srpska).

He loved local folk words. He would choose one and then repeat it to anyone he met that day or that month, as if he were sowing. I once met him three times in one day and each time he mentioned the world venturer. He was actually a venturer: hardworking, diligent, entrepreneurial man (Dictionary of Matica Srpska).

In the Raskovnik desk, we were preparing the ”Kosovo edition”. An abundance of material promised a double or triple issue, but the director of Narodna Knjiga publishing, otherwise a brave man and publisher, asked the magazine Board for their opinion. The Board included professors, writers, employees of Narodna Knjiga and ”social-political workers”, as the ”conscience of the society”…

Dragiša was a careful presenter, particularly literate and respectful writer and speaker – he interpreted the ”Kosovo edition” and explained its subjects and authors… The magazine Board concluded that the edition had to be reduced, and certain subjects and authors omitted due to the ”fraught political situation” and course of the Communist Union… Dragiša raised the large pile with the manuscript of the ”Kosovo edition” from the table and threw it on the ground as a sign of protest. It was his only expression of rage and powerlessness.

The edition was, although reduced and altered, published. Even as such, it is a valuable document, full of excellent texts, but Dragiša had never recovered from it. He realized that full freedom and truth will not be achieved during his lifetime.

SON OF THE EARTH

He said he would remain editor in chief, only in case Zoran Vučić, the youngest peasant poet from Bučum in Tresibaba, is hired and given a salary as the magazine secretary in Narodna Knjiga publishing. A poet of world darkness, with an equal view of the Kolarac and Miroč. Dragiša wrote about Vučić’s first poetry book in Borba in 1977.

He said he would remain editor in chief, only in case Zoran Vučić, the youngest peasant poet from Bučum in Tresibaba, is hired and given a salary as the magazine secretary in Narodna Knjiga publishing. A poet of world darkness, with an equal view of the Kolarac and Miroč. Dragiša wrote about Vučić’s first poetry book in Borba in 1977.

The Raskovnik desk didn’t have its own office. We used to meet in Dragiša’s little study, full of books and magazines, or in the ”Đorđe Jovanović” Library, on the ground floor of the building in Studentski Trg where Dragiša lived. Or a bit lower, in Zmaja od Noćaja Street – in the humble old-fashioned kafana Komunalac. The manager of ”Petar Kočić” Library, Danica Lala Jevtović, also member of the Raskovnik group, also often opened the doors of her library for our desk meetings.

One year, in only a few evenings, the same Momir Vojvodić from Titograd wrote the long poem ”Battle of Kosovo” – in rhymed decasyllabic verse. I brought it to Raskovnik. Professor Vladeta Košutić didn’t agree with my evaluation that the poem is excellent, but still cannot compare to Vuk’s Kosovo cycle poems. He thought that the poem was on the level of Vuk’s… We printed it in Raskovnik, but separately from the magazine, as a separate booklet, with a total circulation of 8.000 copies.

Dragiša wrote the chronicle of literary and publishing events in Raskovnik. He believed that everything from literary life should be noted and thereby preserved for future researchers and literary historians. Thus – he used to say – with the help of short notes in Serbian Literary Herald you can discover much about writers and their works, subjects and events of past times and forgotten people.

The first and permanent support Dobrica Erić received from Dragiša Vitošević. The literary scene of Serbia and Yugoslavia always attempted to follow certain fashion trends. Under the excuse of modernity, many hid themselves in actual isms which determined the editorial policy of both publishers and magazines. Erić’s lavishing world didn’t fit in the Chronicles of Matica Srpska either – he waited an entire decade for them to decide to publish his poems, which did include pastorals and fairground colorfulness, but also confronting the earth which gives birth and accepts, which sends farmers, warriors and poets under the same flag of Boško Jugović, still waving after the sacred Battle over the sacred Field. Dragiša Vitošević, erudite, knew to interpret and defend the dimensions, colors and shades of rural poets (not only Dobrica Erić, Milena Jovović and Srba Mitić). As a sign of gratitude, after his friend’s death, Dobrica dedicated the ”Black Scarf over Bare – Memorial Service to My Friend Dragiša Vitošević” songbook, including six sincere poems.

In the first poem, he equates Dragiša with Vuk Karadžić:

He was Vuk, in spirit and body

he was Vuk, in body and dressing

he was Vuk, in idea and principle

without Vuk’s crown on his head…

In the ”Lament”, he lists Dragiša’s books:

You’re beyond all your worries

and completed Serious Games.

Now you’re lying under willows

a butterfly flying over fields

and Orpheus among Plums is crying(...)

Is your mother talking now

to Contributors from the Shadows?

A ”Postmortem Conversation” is entitled ”Downstream from the Sun”. It begins with the verse:

Three days of black birds, three nights of black roses

Three centuries of my head napping under a black star

Did I just dream about a black flag amidst our green Gruža

Or you, Dragiša, my brother, are really gone?

The poem ”Funeral of Dragiša Vitošević” reminds of Erić’s ”Farmer’s Funeral”. Then comes ”How Dragiša’s Family Laments” and, at the end, ”Candle on the Grave”:

Near a sunflower field

far from the capital city

and other cities throughout the world

where his face used to shine

rests Dragiša

relentless and agile.

Now Erić is also resting next to his brother and parents in Gruža, and his entire poetry – is his epitaph.

***

The Hunt

– We were running around the entire day chasing hayduks – tells me uncle Voja Nikolić from Dobrača, former policeman. – Agony! And nothing. And when we finished the hunt, off to dinner.

The president of the village was a good host, two nice houses in the yard. We were sitting in one, having dinner and speaking about hayduks all night, and in the other – hayduks were having dinner.

(From the book Oxen on the Ceiling. A Hundred Short Stories, Belgrade, 1996)

***

Commissioner’s Son

The commissioner passionately prosecuted communists and destroyed their books, brochures and pamphlets.

He left only one copy for himself, thus making a large, rare collection, which he cared about a lot. It was proof of his diligence and genuine battle trophies.

One day, among the arrested communists, as one of the ”most poisonous” ones, the commissioner’s son was standing.

(From the book Oxen on the Ceiling. A Hundred Short Stories, Belgrade, 1996)